| ABOUT | ART WORKS | TEXTS | CONTACT |

|---|

ARNOLD SHARRAD

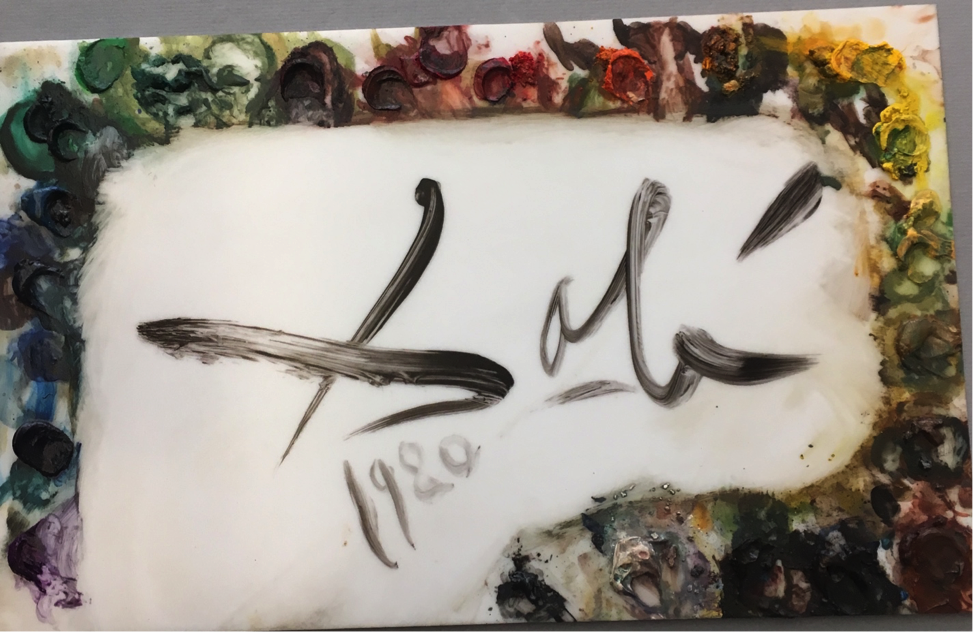

Arnold Sharrad: Some Observations Arnold Sharrad was born in Odessa, Ukraine then part of the Soviet Union in 1946; he left for the United States in 1974; and died in Brooklyn, New York in 2015. These are the dates for an artist like thousands of others in the Soviet Union who left home simply to pursue art in an environment free from the unrelenting control of the Soviet system that brooked no departure from official state style and its suffocating, conformist, socialist realist message. There is nothing simple about what they did and there is something heroic about their willingness to leave friends, family, and familiar places behind in order to be free. America welcomed artists who sought refuge hoping to practice their art and to create a new life. Some of them found their way, others struggled. Arnold Sharrad was one of the latter. Greg Kapelyan's eloquent, moving biography and conversations with Sharrad’s close friends make it clear that he struggled to find his way in this new environment as he was temperamentally unsuited for self-promotion. Perhaps he was too proud to undertake the effort necessary to find "success." And by success I mean pubic recognition and the financial gain that comes with it. After all, isn't this the standard by which "success" is most often measured in the art world? Greg Kapelyan tells us that Sharrad lived like a "hermit" in his Brooklyn apartment content to work for himself, unwilling to engage in the rough and tumble of the New York art gallery scene. Kapelyan writes "once he [Sharrad] was asked: "If you could arrange the ideal way of life for yourself as a painter what would it be?" - "I would have gone to the desert. To fast, pray, and paint." His answer may have been quixotic but in essence this is what he did in his own urban wilderness. What we hear from friends who knew and loved him was he was utterly devoted to his art. Herein lies the true measure of his success for how many of us can say we are totally happy with our lives? As for hermits, let us not forget they were visionaries who enjoy a special place in the Western mind and heart not only for their asceticism but especially for wisdom and spiritual purity accrued through harsh abnegation. Like St. Anthony, the best known of the early hermits who retreated to the Egyptian desert in the early years of the Christianity, Sharrad too retreated - but to his apartment in Brooklyn. This is not to say that he was a recluse: Far from it. Sharrad had to earn a living and was employed over the years in a number of art related jobs especially as a restorer. While working for a firm in 1980, he met Salvador Dali who admired his work, signed Sharrad’s palette, and was photographed with him (Figs. 1, 2).

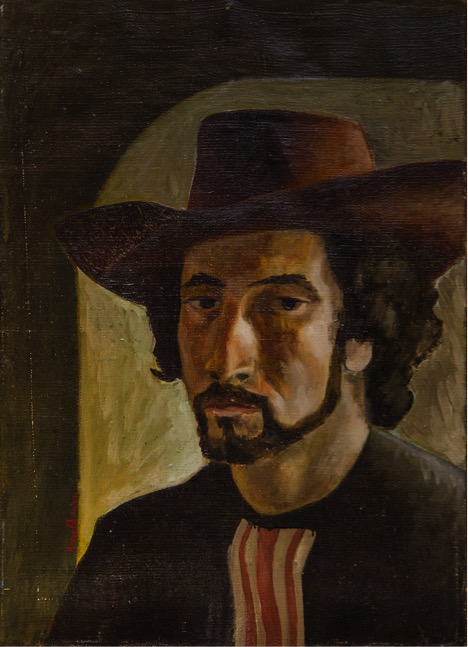

Sharrad’s style and subject matter in the early 1970’s was far from the official norms of Socialist Realism. Still-lives and portraits, often self-portraits, were rendered in a simplified, abstracted style that understandably carried over to his early work after his arrival in New York in which he explored aspects of his Jewish heritage (Figs. 3, 4, 5).

From there he evolved to a completely new style in poured painterly abstraction whose generous use of colorful paints on a blank ground recall the work of artists inspired by Joan Miro and Pollock’s gracile poured canvases (Fig. 6, 7).

These rapidly executed colorful works soon gave way to a totally new and surprising direction. Large, impressive, spare almost monochromatic paintings whose dark, Caravaggesque backgrounds framed simplified, inflated, Botero-like objects and people in surrealistic settings (See Figure 8). These images, dark in form and content, signaled expanded ambition and a critical analysis of the world as one sees in his large painting of a pedestal with a curious appendage at its center and a TV floating above in an aureole of golden light, perhaps a comment on the materialism worshipped by Western society.

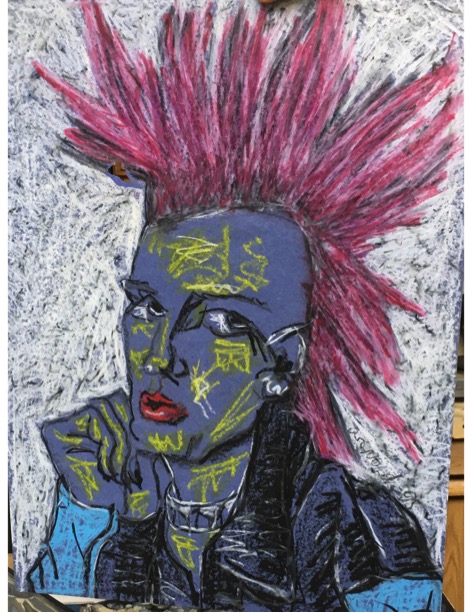

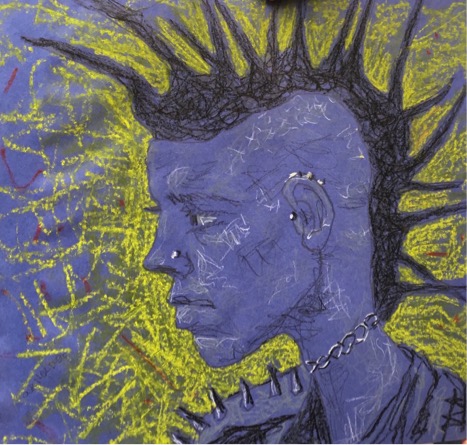

However, it was the punk culture of New York’s East Village and its angry, confrontational anti-materialism that struck a resonant chord. Here Sharrad found characters colorful, inspirational, and liberated, a liberation that led to a change in style as radical as the punkers he depicted. Abstracted, geometrical, painted portraits were an early indication of this new interest images that are allusive of Malevich’s late portraits of peasants(Fig. 9).

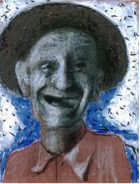

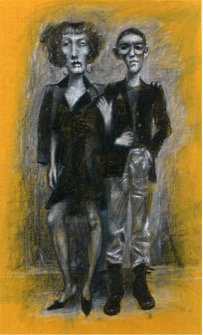

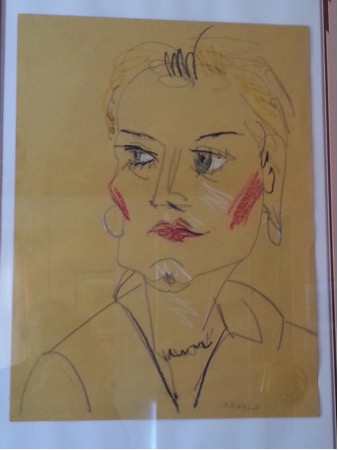

However, it is especially the large, freely executed, strikingly colorful and insightful portrait drawings that heralded a fresh new vision (Fig. 10, 11). A vigorous graphic style, multilayered defined by rapid scribbles and thick webs of intersecting lines often in mixed media created a dynamic calligraphic style charged with a dramatic, startlingly fresh energy. Faces were often set against contrasting colored backgrounds rapidly sketched or heavily worked providing a blank relief-like ground against which the figure emerged as if from an infinite space. Rarely, if ever, did Sharrad set his subjects in a landscape or an identifiable location. His aim was to focus solely on person and personality without the distraction of subsidiary settings. This intense focus, the simplified “naïve” style he soon adopted, and the masterful handling of materials - pastel, oil stick, charcoal, and paint - create an allusive ambience, an aura surrounding those portrayed that seems to elevate them to another realm, one separate from the everyday world. As we will see, that style was refined and perfected over the last 15 years of his short life.

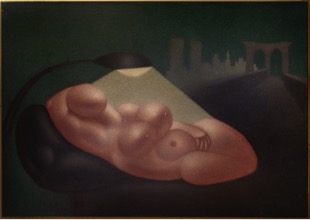

This is the period I want to address - to me it is the most compelling. When asked to write something about Arnold Sharrad my initial reaction was to decline – after all what can be said about an artist one never met and whose work is known only through photographs? When I do write an appreciation of a contemporary artist I want to meet him/her; visit the studio; see the work up close. Of course, in this case that was impossible as the artist has passed away, his work is in New York, and I began writing from Rome where I now live. But a closer review of the photos changed my mind and finally seeing the work in the flesh was revelatory. It seemed to me that Sharrad found his path in the late paintings creating a body of work, predominantly portraits, filled with empathy, compassion, humor and astonishing psychological insight. Images of everyday people; colorful characters; happy, proud, stylish, troubled, down and out, the homeless the hopeless; street people on the fringe of polite society who all too often we try to avoid. Sharrad was clearly inspired by the city in which he lived and the people he encountered and painted. But what were the influences shaping his vision in the late work? What images from the history of art did Arnold Sharrad have on his apartment walls; what art books did he own; what Old Masters did he favor; what modern and contemporary artists did he admire and why? What do his sources tell us about his motivations? These are questions I cannot fully answer. Nevertheless, our collective memory of the history of art inevitably calls to mind sources we know that inform and enrich our interpretation and understanding of his final years. Arnold Sharrad may have been a "hermit" in a certain sense, but he lived in New York, the center of the art world and he clearly drew upon the diversity of images that history offered absorbing and transforming them in the late pastel and oil stick images of people and paintings of places where he found inspiration. It is interesting to note that he was also a collector of Asian art and, perhaps not surprisingly in light of his personal style, of naïve art, two areas that could be said to lie at the opposite ends of the collecting spectrum yet which demonstrate the expansive nature of his personal taste and a refined sensibility for a wide variety of expressive potential. In fact, since beginning this essay I have learned Sharrad was indeed very knowledgeable about art history, a fact that comes as no surprise. One does not need to be well versed in Renaissance art to see the direct connection between Sharrad's Reclining Nude and Giorgione's painting of the same subject, a painting that started a long series of reclining nudes throughout Western art history. (Figs. 12, 13)

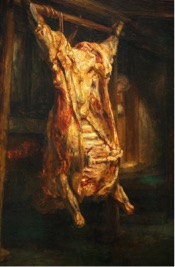

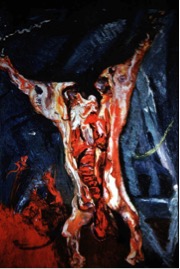

But what a difference in the handling of the body! Sharrad's Venus is formed by a series of swelling bubbles abstracting and exaggerating body parts – head, neck, breasts, and stomach - and most surprisingly legs that have morphed into the head of a circumcised penis. This “hermaphroditic” figure set on a black couch at the beginning of the Brooklyn bridge's walkway basks in the glow of a goose neck lamp with the once familiar skyline of lower Manhattan silhouetted against a dark evening sky - no sunny pastoral, rolling landscape here -rather an allusive nocturnal dreamscape. What did the artist have in mind when he painted this hybrid figure; the fusion of female and male sex in an icon of erotic desire; an emblem of sexual satisfaction on the path to the promised land; a midnight dream of desire's personal gratification? The answers to these questions are illusive but when looking at Sharrad’s work as a whole, how do the subjects he chose to paint help us understand the the ideas motivating him? We read in Greg Kayelyan's essay the following comment made by Sharrad: “I always felt that there was some force to watch me, evaluate my actions, thoughts, approve or disapprove them. And I began to relate my life with this force. In Lviv, there are a lot of kościółs [Polish catholic churches], and I often visited them, always feeling there a warm kind of vibration.” When he was asked if he could feel the same warmth in a synagogue (Arnold was Jewish) he said: “Yes, there is no difference: a synagogue, a Catholic or an Orthodox church”. Saints Anthony, Jerome, Francis retreated to the wilderness where isolation aided their search for spiritual enlightenment, for a force to guide them toward inner peace. Sharrad's observation about discovering "a warm kind of vibration" in churches of all religions offers a key to understanding what must have been a deep, universal faith. His "Crucifixion with Side of Beef" calls to mind a Crucifixion by Rubens as well as Rembrandt and Soutine's famous images of a flayed animal carcass, difficult paintings at once repellant and attractive (Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17).

upward in despair, the tiny wailing Mary Magdalen below the hanging Christ/carcass; the jagged folds of frumpy jackets and pants and wandering eyes of the three standing men (soldiers?) who in their distorted, disturbing rendering are oblivious to the momentous happening. By substituting a carcass for the body of Jesus, Sharrad emphasized in a most unusual way Christ's carnality, His humanity. There may be prototypes for this idea but I am unaware of any. Gray, the color of death defines all of the figures while three red poles lead the eye upward to the brilliant hemisphere of golden, heavenly light signaling the miraculous nature of the event and of the flesh sacrificed below, a sacrifice ensuring man's salvation. Surely here the "force" that the artist spoke of watching over him expresses itself.

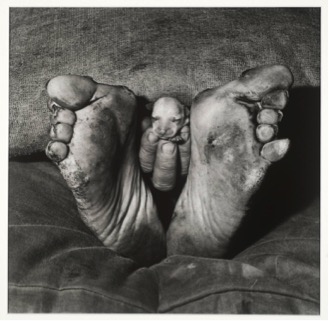

What do we have here? It appears to be the image of a dead man covered with a bright red cloth lying on a metal mortuary table lit by two triangular light fixtures. The large feet, also red with greenish tint at the sides, fill almost half of the canvas and are marked by two dark ovals on the soles. This strange image might at first call to mind Diane Arbus, an artist whose work he surely knew as we will see shortly, and her curious photograph of large, dirty feet with a new born puppy emerging from a hand between them (Fig. 19).

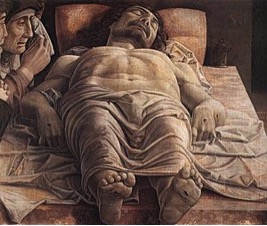

However, much closer to the mark is Mantegna's image of the dead Christ whose radically foreshortened body is observed feet first (Fig. 20).

On those feet nail holes are clearly visible. There is no doubt in my mind about Sharrad's allusion to Mantegna's painting, as well as others like it, and its salvific content. Yet, unlike Mantegna who painted Christ in the gray pallor of death, Sharrad used a bright, blood red suffusing the area above and below the table, no doubt a symbolic, sacrificial red. This is not to say that Sharrad is proselytizing, far from it, only that whatever the impetus to create his painting, he found in Mantegna a chord resonant with the "warm kind of vibration" he experienced in sacred places. Perhaps this spiritual vibration helps to explain a rather unusual painting of a large fish (Fig 21). Rising from the water under a turquoise morning sky, sun glowing in the distance, is a fish seen from below, gills and head above the surface, body below. It seems unlikely that Sharrad was celebrating a successful fishing trip. Rather when seen in connection with the two previous paintings this fish may be understood as the well-known emblem of resurrection and salvation.

Characteristic of the majority of Sharad's work is his emersion in the urban environment. Buildings served as objects for expressive analysis and remarkable insight. His small, joyful paintings of Brooklyn streets seethe with a roiling energy heightened by thick, icing-like impasto. Buildings are askew, their shapes distorted by some strange force setting them swaying wildly under a Van Gogh like sky (Fig. 22).

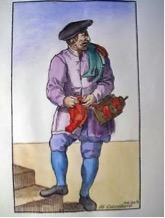

Sharrad's dynamic cityscapes recall Soutine's paintings of villages that seem to come alive as if marching across the landscape in a tightly packed, jumbled parade formation. Both artists used paint in a vigorous, expressionistic style creating an anthropomorphic character to buildings devoid of human inhabitants yet vibrantly alive, animated by the pulsing energy of the city (Fig. 23). Exuberant and charming, these miniature urban sketches are among Sharrad’s most delightful creations. This is not to say Sharrad was oblivious to the denizens of his neighborhood – far from it – he was a keen observer of life around him. In this respect, some of his paintings recall the early work of Annibale Carracci whose interest in the quotidian initiated a reform of Italian 16th century painting. Drawings of the professions of Bologna, 80 works now known mostly from engravings, chronicled the people who walked the streets hawking their wares. This interest in street people is evident in many of Sharrad's paintings (Fig. 24).

We can readily see the similarities when comparing these works to Carracci's wandering merchants such as his drawing of a chimney sweep and print of a weaver of socks (Figs. 25 26,). The man in Figure 24 might well be taken for a candle maker offering his wares to passersby at a Brooklyn Street market. Any number of Sharrad's portraits capture, in arresting ways, the unusual, the cheerful, and often haunting dignity of neighborhood people who willingly faced his sketch pad or allowed themselves to be photographed as the first step in their metamorphosis from realty onto canvas (Fig. 27, 28).

An especially enchanting image is a charming depiction of a lovely, stylishly dressed young woman proudly posed prettily, left arm at her side, eyes glancing to the right with a captivating air, elaborate coiffeur, and the delightful insouciance of an idealized Italian peasant girl in an equally stylish outfit seen in Edmunde Jeaurat's engraving of about 1710 (Figs. 29,30).

I am not suggesting that Arnold Sharrad went hunting for Old Master sources when creating this painting. However, it is fascinating to see how often subtle insights of his predecessors are present in his best work, proof at the very least, of Sharrad's skill at identifying and capturing the physical and psychological traits that make his portraits so compelling.

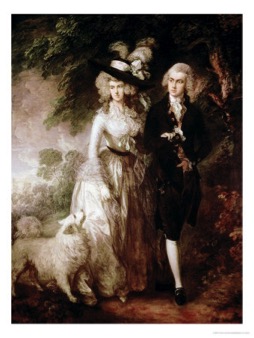

Sharrad's couple possess the easy grace associated with 18th century portraits of Britain's proud, well-healed Lords and Ladies whose social supremacy and self-confidence ooze out of every pore. All that is lacking in Sharrad’s portrait is an adoring dog gazing reverentially at its masters. As noted above, Sharrad's late drawings exhibit a vigorous use of line and expressive color. His paintings are no exception as we see in the hot reds and pinks of the dangerous ballerina in Figure 34 and in Figure 33 where flesh is acid green; effects imparting a provocative, disturbing aura. Why is this person’s face green; what did the artist have in mind when choosing this color; what did he see that led him to depict her with green skin and a head far too large for her body? Whatever the reasons, the results are arresting and compel us to linger over the portrait to wonder, not that there is any one answer.

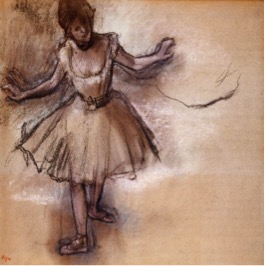

His dancer in a pink tutu is not the lovely, graceful ballerina that we see in Degas' drawing, a charming delightful young woman whose beauty and grace make us smile (Figs. 34, 35).

Her tilted head, one drooping eye fixing us with a knowing stare; lipstick askew; spread legs, skirt raised high revealing the punctuated Venusian cleft offers an arresting image of woman as sexually accessible, a dangerous predatory being at once alluring and frightening like the sibyls who tempted Ulysses as he traversed the Straits of Messina. One wants to approach but woe to him who gets too close! Here Sharrad’s color palette calls to mind Matisse’s Fauve period, as in the Portrait of Madame Matisse from 1905 where erratic areas of scumbled paint surround the seated figure in a jarring surround of paint patches perhaps inspiring Sharrad’s mandorla of toxic reds, pinks and greens framing his dancer (Fig 36).

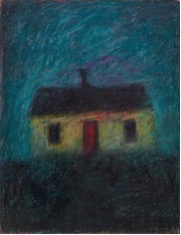

A city is a place where one can be alone in the midst of thousands of people who pass you by every day without a word of greeting, neighbors who are total strangers for years on end. Perhaps no one captured urban loneliness and isolation more poignantly than Edward Hopper. His images, whether of buildings or people seen through diner windows at 2 am as in Night Hawks, are icons of alienation and sadness. Inhabiting his apartment/cave, Sharrad undoubtedly witnessed and himself empathized with those alone and anguished. His painting of a small house on a hill bears an eerie resemblance to Hopper's watercolor of the same subject (Figs. 37, 38).

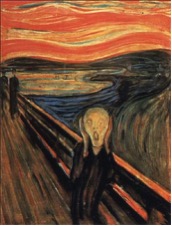

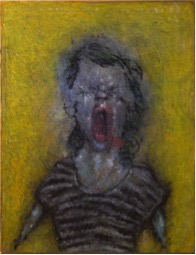

Hopper's house, silhouetted against the afternoon sky, is shuttered, it's front door boarded shut, abandoned and bereft of occupants. Sharrad's stripped down, small cottage rises against the dark night sky, foreground also barren, appearing for all the world like a spooky, haunted presence with a sad, lonely life of its own - a reflection perhaps of his own alienation. Indeed, many of his paintings express profound pain, the anguish of the incessant battle to make our way in the world, often under the most trying and unbearable circumstances. All too often we want to scream, as in Edvard Munch's The Scream and Sharrad's three paintings of the same subject (Figs. 39, 40,41, 42).

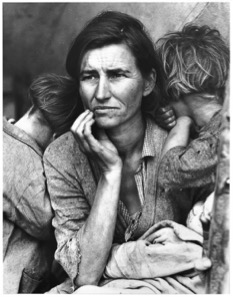

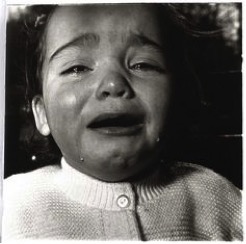

or cry under the burden of caring for a child without support (Figs. 43,44).

Dorothea Lange's photograph of a weary migrant mother and her children resonates powerfully in Sharrad's portrait of a crying, troubled young mother, hand to face, grasping her infant as she struggles to cope with the overwhelming challenges life throws at them.

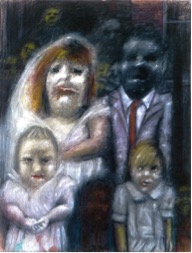

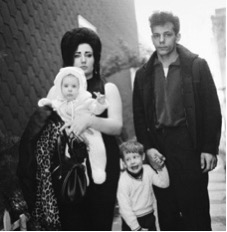

His portrait of a family of four (at a wedding?), each person carefully observed and skillfully characterized is a masterpiece of psychological observation and bears an uncanny relationship to Arbus' photo of a husband, wife and their two young children, the son's expression offering a startling prototype for the little girl at the right in Sharrad's painting (Figs. 47,48). As noted above, he sometimes worked from photographs here most likely from one taken at a reception. He may well have been familiar with Arbus' work and this photo in particular.

Yet even if he knew it, he saw the strange beauty in this group pose at that moment and made it his own. Although he may have used photographs and been inspired by artist’s like Arbus, Sharrad did not paint in a photographic manner. Rather as noted, he favored a “naïve” sometimes cartoon-like figural rendering with outsized heads and dramatic expressions. In many ways his style recalls German Expressionism’s simplified, non-naturalistic figures rendered in bright colors, figures charged with an intense emotional tension as seen in paintings of The Scream and others discussed above. Inner emotional tumult is also expressed in a vigorous gestural handing of materials. His painting and graphic style is agitated, nervous and layered in the way he built up faces and figures in overlapping zones of color – a palimpsest. His treatment of the background, although usually “blank”, is textured by color and an engaging graphic handling setting off the figure. The connection with German Expressionism may have been stylistic but as we conclude by recalling Sharrad’s subjects over the last two decades of his life there is the unavoidable realization that we are faced with a man of great empathy for the people he portrayed. Sharrad was not a social critic like the German artists of the Weimer Republic. Rather in his paintings and drawings he expressively brought forth his subjects’ inherent dignity, even when recording their anguish or pain.

|

|---|